Data Center Power in Virginia: The Questions HB 897 Doesn’t Answer

“Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.”

- H. L. Mencken

Virginia keeps pouring concrete for data centers like the pace is normal.

It isn’t.

Every new campus brings the same physical stuff we’re all familiar with. Big pads, big yards, big gear. And then the part that is not concrete, but drives a lot of the concrete: power.

HB 897 shows up right in the middle of that problem, and it’s worth reading with a skeptical eye. Not because there’s some perfect alternative. There isn’t.

There are only tradeoffs.

HB 897 ties Virginia’s data center sales tax exemption to new energy conditions. One of the main conditions is that, to keep the exemption, a data center cannot use co-located generating facilities that emit carbon dioxide, except backup generators.

That one sentence creates a bunch of downstream questions that the bill itself doesn’t answer.

First question: what does “co-located generation” mean in practice for a hyperscale load?

Most people hear “microgrid” and picture a couple of solar panels and a battery.

That’s not a data center.

A hyperscale campus is a steady, 24/7 load that does not politely shrink because the weather changed. If you want on-site power that can actually run it, you’re usually talking about gas generation, often in a configuration that could operate as prime power.

HB 897 doesn’t ban that outright.

It just makes it hard to justify financially if the exemption is worth more than the on-site generation strategy. And the exemption is not small, so the incentive is real.

So the bill is trading something. The question is what.

Second question: if you discourage on-site firm generation, where does the firm power come from?

The bill pushes developers toward the grid as the primary supply.

That sounds fine until you remember what the grid is in Virginia. It’s a regulated utility structure. In Northern Virginia, Dominion is the dominant utility serving the exact area where most of these data centers are landing.

So if you make on-site prime power less attractive, you are implicitly making the utility grid more responsible for serving the load.

Is that the intent? Maybe. Maybe not.

But it’s the likely effect.

Third question: what does that shift cost, and who pays?

If the grid is going to carry more of the data center growth, the grid needs more infrastructure. Feeders, transformers, substations, interconnection upgrades, transmission planning, replacement cycles. That’s real work. Real material. Real time. Real permitting. Real outages during tie-ins. Real schedule risk that contractors and owners have to live with.

Utilities don’t build that infrastructure for free. In a regulated model, capital spending typically flows into rates over time, unless regulators force a different allocation or a project is structured so the customer pays directly.

So one of the tradeoffs HB 897 is making is shifting responsibility for reliability and expansion away from the site and toward the grid.

That can be a reasonable choice. Central systems can be efficient.

But it also raises the uncomfortable question: how much of the upgrade burden ends up socialized onto ratepayers who do not get the benefit of the data center buildout?

If your answer is “none,” I’d like to see the mechanism that guarantees that.

Fourth question: what happens to backup generators when the grid is doing more of the heavy lifting?

HB 897 allows backup generators. That’s important because it means nobody is pretending generators disappear.

But here’s the skepticism: if you increase dependence on the grid, you increase the importance of backup generation, because the consequences of a grid event are bigger.

A data center doesn’t “ride it out.” It transfers load and keeps going.

So the tradeoff might not be “less generator impact.” It might be “different generator impact,” with more reliance during grid stress events.

If the policy goal is emissions reduction, you at least have to ask whether discouraging prime power and increasing grid dependence unintentionally increases runtime risk for backup fleets during constrained periods.

Not guaranteed. Not doom. Just a real question the bill doesn’t answer.

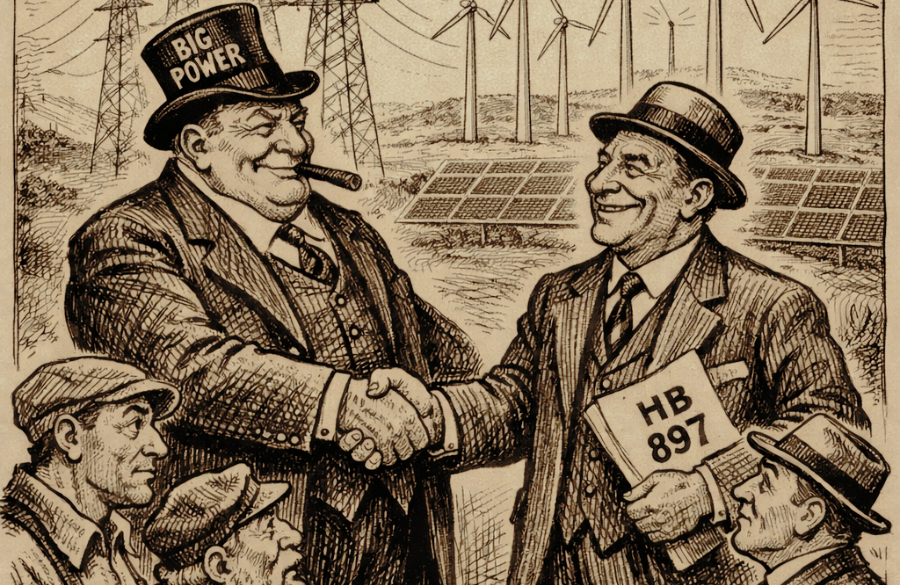

Now, the political background matters only because it helps explain why this bill looks the way it does.

HB 897’s patron is Del. Rip Sullivan (D–Fairfax).

The list of Democratic co-sponsors includes Del. Kacey Carnegie, Del. John McAuliff, Del. Irene Shin, Del. J.J. Singh, Del. Betsy Carr, Del. Rae Cousins, Del. Elizabeth Guzman, Del. Karen Keys-Gamarra, Del. Michelle Maldonado, Del. Kathy Tran, and Del. Vivian Watts.

It passed the House 61–34.

That’s not a judgment. It’s just the landscape: this is a Democratic-led approach to a specific issue, and it reflects a specific set of instincts about how to handle big loads.

There’s also a funding ecosystem around Virginia energy politics that’s been shaping bills for years.

Clean Virginia is a political organization heavily associated with Michael Bills, a Charlottesville investor. Bills’ stated aim, through Clean Virginia, has been to reduce monopoly utility influence in Virginia politics and policy. Clean Virginia operates through PAC activity that supports candidates, and that has become a meaningful lane of campaign support in Virginia energy debates.

Again, this isn’t about picking teams. I don’t trust politicians as a category and I’m not excited by the idea that more laws automatically produce better outcomes.

But if a bill is trying to steer the market, you should understand who is steering and what their incentives are.

Which brings us back to the core skepticism.

HB 897 looks like an attempt to use a tax incentive to steer data centers toward “cleaner” energy behaviors.

But it also appears to trade off local self-sufficiency for grid reliance.

It trades off developer-controlled firm power options for utility-controlled supply planning.

It may trade off one kind of emissions profile for another kind of reliability strategy.

And it may trade off some level of competition in power supply for deeper dependence on the monopoly utility system.

Are those good trades?

Maybe.

But they’re still trades.

So here are the questions I think engineers, contractors, owners, and ratepayers should be asking before anyone acts like this is obviously “smart” or obviously “stupid”:

If we discourage on-site firm generation, what is the actual plan for firming intermittent resources for 24/7 hyperscale load?

If the grid is expected to handle more of this growth, what infrastructure is required, on what timeline, and under what cost allocation?

What portion of new infrastructure is directly assigned to data centers, and what portion is rolled into general ratepayer recovery?

If backup generators remain allowed and necessary, how does the bill change actual generator runtime risk during constrained grid events?

If the stated goal is reducing monopoly utility influence, does increasing reliance on the monopoly grid move that goal forward, or backward?

If the stated goal is decarbonization, are we measuring actual physical outcomes, or compliance mechanisms that look clean on paper?

None of those questions have perfect answers.

But pretending they don’t exist is how we end up with the worst kind of infrastructure policy: confident, expensive, and surprised by the consequences.

There are no perfect solutions here.

Only tradeoffs.

HB 897 is making some. We should at least be honest about what they are.